I’ve been devouring several books on education theory recently (Poetic Knowledge: The Recovery of Education by James Taylor, Leisure: The Basis of Culture by Josef Pieper, and Consider This: Charlotte Mason and the Classical Tradition by Karen Glass), but one in particular has me breathless. I want to stop and savor this one a while.

Stratford Caldecott’s masterful treatise on education, Beauty in the Word: Rethinking the Foundation of Education is my new favorite book on education theory. Inspired by Brandy Vencel and her chapter-by-chapter discussion of The Liberal Arts Tradition (a book I have not read, but I intend to do so after following Brandy), I will do the same for Caldecott’s book. In this series, I’ll comment on each (probably each . . .) chapter in the book, particularly from my perspective as a Catholic Charlotte Mason homeschooler.

Caldecott, who died only recently from cancer, was a respected scholar at Oxford. The editor of the UK edition of the Magnificat, he was also solidly Catholic. So, we are in good hands here. Of great interest to me, he admired Charlotte Mason and even devotes a section of chapter six (entitled “Learning in Love: Parents as Educators”) to her. Caldecott says Charlotte can offer modern parents and teachers “a feast of wisdom” (126). More on this to come when I cover that chapter.

What Is Education?

Let me begin by stating Caldecott’s thesis:

[E]ducation is not primarily about the acquisition of information. It is not even about the acquisition of “skills” in the conventional sense, to equip us for particular roles in society. It is about how we become more human (and therefore more free, in the truest sense of that word) (11).

Education is about becoming more human, becoming more free. How do you educate a child’s humanity? Caldecott answers this question with the three arts of language: grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric. That’s the trivium, which I thought I had left long behind when I became disenchanted with the classical movement in homeschooling, but Caldecott has piqued my interest again. He spends separate chapters on each “art” so we get a good idea how this kind of education is supposed to happen.

I note immediately that Charlotte Mason asks the same question about education; it is her starting point. She starts with the principle that children are born persons, and that matters to me as a Catholic parent seeking to educate my children’s hearts and souls, and not just their heads. It means she is proceeding with the assumption that the dignity of the person should be protected and honored. The whole person.

Caldecott’s Trivium

Caldecott’s explanation of the trivium is a refreshing break from the way I’ve understood it in the writing of some modern classical homeschool advocates.

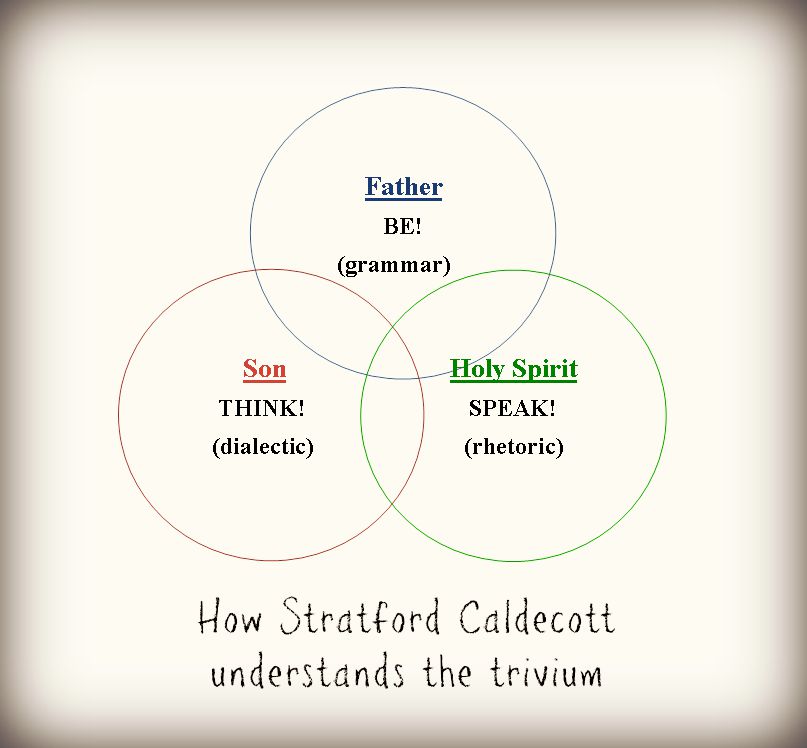

For Caldecott, these three “arts” — grammar, dialectic, rhetoric — have always been Trinitarian in nature; they are interwoven and connected not only theoretically, but metaphysically as well. He is not producing an abstract theory (though admittedly the discussion can become abstract); he is trying to describe reality – the reality of what it means to be a human moving toward God.

Here’s a basic snapshot of what he’s getting at. The art of Grammar is about being, about remembering our origin and end in the Father, where we came from and where we are going. The art of Dialectic is about right thinking, about recognizing truth, about walking in the light with the Son. (This art reminds me of Charlotte Mason’s “Way of Reason”.) The art of Rhetoric is about speaking, about sharing the truth in communion with others through the Holy Spirit.

I’ll unpack this view of the trivium in 3 separate posts, following Caldecott chapter-by-chapter. Observe, though, how his presentation differs from Dorothy Sayers’ explanation of the trivium in “The Lost Tools of Learning.” Her version has become almost unquestioned in the homeschool community, but Caldecott provides some food for thought.

For Sayers, the grammar stage (called the poll-parrot stage) is about memorizing stuff because kids are so good at it — she wants to get the basic facts into kids’ heads. The dialectic or logic stage is about putting the facts the kids learned into a recognizable framework. The rhetoric stage is about making powerful, effective arguments.

I can see one clear difference between Sayers and Caldecott immediately. Sayers version is about the content of the curriculum and the developmental stage of the child. Nothing wrong with that, and I am sure Caldecott appreciates these aspects of a good education, but he sees something more profound at play. While Sayers is focused on the developmental job the child is mastering in each of her stages, Caldecott’s trivium is very relational: the child is moving through stages of relating to The Good, The Beautiful, and The True not just through topics or subjects studied, but through his relationships with his family, strangers, and God.

The Science of Relations

Every time I read the word “relational” in Caldecott, I recall Charlotte Mason’s principle “education is a science of relations.” When Charlotte uses the term “relations” she is talking about the capacity of a child to make connections between ideas and things she’s studying. Here is how Ambleside Online paraphrases Charlotte’s principle:

“Education is the science of relations” means that children have minds capable of making their own connections with knowledge and experiences, so we make sure the child learns about nature, science and art, knows how to make things, reads many living books and that they are physically fit.

I love this aspect of Charlotte Mason’s philosophy, and some recent writers (Karen Glass, in particular, in her book Consider This) believe her “science of relations” has roots in the classical liberal arts. Missing from Charlotte’s “science of relations,” however, is the child’s relationships with human beings and God. Those relationships are critical to a child’s understanding fully everything she is experiencing and observing.

For Caldecott, “relational” definitely includes human relationships. His thinking is strongly informed by “personalism, ” and specifically Catholic personalism. His explanation of this branch of philosophy (which also provides a lot of the muscle in John Paul II’s theology of the body — so foundational to my approach to parenting. It just gets better and better!):

Personalism is a name we give to a philosophy that gives priority to the person as distinct from the individual. Here the “individual” means the particular human being thought of as possessing an identity quite separate from others, and as entering into relationships with them — if at all — by choice. The “person” on the other hand, means the human being determined in his identity (from within, as it were)by relationships both chosen and unchosen (31 and 32).

For Caldecott, the nature of knowledge is relational not just because all knowledge is connected in some way (though Caldecott agrees with this assertion), but because it is spiritual and mysterious in a Trinitarian way. Truth, Beauty, and Goodness can be found by human beings not just through the study of the right topics, but through the giving, receiving, and sharing inherent in God’s creation. With this in mind, he states with confidence what the chief goal of any good educator should be:

A personalist philosophy of education therefore starts from the premise that the human person should be educated for relationship, attention, empathy, and imagination. The school (which receives its authority over children ultimately from their parents) does not exist simply to feed the industrial machine with workers, or the market with consumers. It is oriented towards the family and family life (34).

We educate our children for relationship, attention, empathy, and imagination. If I pressed a bit, I’m sure I would find this personalist impulse in Charlotte. I think it is implicit in her overall philosophy because she 1) prioritizes the personhood of the child and 2) she emphasizes the power of a child’s home atmosphere in shaping his mind and character. For her, home atmosphere has nothing to do with the decorating and everything to do with living together as a family.

In my next post in this series, I’ll tackle Stratford Caldecott’s chapter on the art of grammar: “Remembering: Grammar-Mythos-Imaging the Real.”

Series Index

Beauty in the Word: Catholicism and Charlotte Mason ⇐ YOU ARE HERE

Grammar as Remembering (Part 2)

Logic as Finding Truth and Order in the Universe (Part 3)

Rhetoric: Liberating Others to Choose the Good (Part 4)

More coming soon!

Wow! I haven’t read Caldecott {yet — it’s in the plans} and I had no idea he viewed the Trivium in terms of the Trinity, but that is fascinating. I look forward to reading your series. 🙂

Hi Brandy!

It is absolutely FASCINATING and very important. I can’t wait to dig deeper!

Kim